Nowhere else do sea and land organisms share the same habitat to such a great extent as in the mangrove swamps of the tropical and subtropical coasts. The biotic communities of the mangroves are unique. Here, true terrestrial organisms colonise the upper storeys of the tree and shrub layer, while true marine organisms live underneath them.

- Lighthouse Foundation

- Issues

- Life in the ocean

- Mangroves – masters of survival on salty ground

Mangroves – masters of survival on salty ground

Mangroves are trees and shrubs from different plant families, up to 30 metres in height. There are almost 70 species which are superbly adapted for life in the conditions found on salty shores and in brackish river estuaries. It is species diversity which differentiates the mangrove communities of the eastern hemisphere (including the Indian Ocean and the western Pacific) from the western hemisphere (including the Caribbean and the west coasts of America and Africa). The Indo-Pacific group, which generally forms denser and taller stands, is more species-rich overall.

Filters to combat sea salt

In order to be able to absorb any water at all from the salty brine, their plant cells maintain a very high osmotic pressure. In other words, the salt concentration inside the cell is higher than that of seawater. A complicated ultrafiltration mechanism in the mangrove roots allows the diffusion of water towards the higher salt concentration within the cells, but prevents any intake of salt.

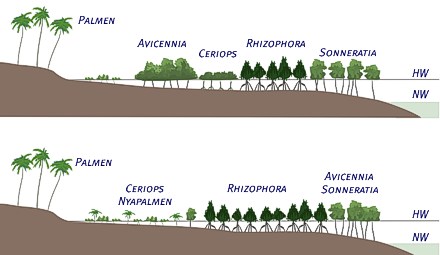

Like cacti, some mangrove plants can also store water (salt succulence) in order to dilute high salt concentrations. In addition, they can shed leaves impregnated with salt, and some have salt glands and salt hairs for the purposes of excreting excess salt. Since the different species have varying degrees of success in coping with the excessive salt levels, moving inland the progressively higher concentrations of salt influence the distribution of species in the mangrove forest.

Specialised root system

All mangrove fruits and offshoots can float, and have developed different strategies to ensure successful reproduction. The fruit germinates while still attached to the tree. There it grows into a cigar-shaped seedling of considerable size, with the first roots and leaves already developed before it falls into the water. It drifts until it lands in a suitable spot, where it takes root.

A characteristic feature of mangrove swamps, however, is the dense mat of buttress, stilt and knee roots. While providing a habitat for numerous marine life forms, these also anchor the plants in fine, loose soils and on hard substrates alike. In among them, countless spiky suckers project upwards from the silt. Because there is no oxygen in the sludgy soil beyond the top few millimetres, these shoots contain vital respiratory organs called pneumatophores. Without them the roots would die off.

Habitat diversity in a confined space

Compared to the unvegetated tidal flats, the dense mangrove root systems multiply the available space for other organisms, offering them a large number of microhabitats in a confined space. Countless fish, crustaceans and bivalves populate the water. The roots of the trees are colonised by algae, barnacles, oysters, sponges and molluscs. In the free-flowing channels, pistol shrimps and fish abound. Large numbers of fiddler crabs are found on the silt surfaces.

The upper storeys of the mangrove forest overhead are home to reptiles, birds and mammals. Sea cows head for the sheltered mangroves to calve, and monkeys venture onto the shore to catch crabs. Numerous water birds including cormorants, kingfishers, ibises, herons and frigate birds take advantage of the rich pickings, and nest in the treetops.

Mangroves, together with coral reefs and tropical rainforests, are the most productive ecosystems on earth. Their falling leaves, flowers and fruits supply more than three kilograms of organic matter per square metre per year, to be decomposed by bacteria and fungi and returned to the food chain. Small fish, shrimps and invertebrates feed on this detritus, which is enriched with micro-organisms, and they in turn become prey for other organisms.

Suspended matter from the mangroves is washed out to sea with the tides, providing nearby coral reefs and sea grass meadows with organic material. Meanwhile the sheltered waters between the roots provide ideal conditions for the larvae and young of numerous fish species.

Highly endangered

An estimated 50 percent of the mangrove forests that once existed worldwide have been destroyed in recent decades. Traditionally, mangrove wood has been cut for use as fuel, charcoal or tanning materials. But the removal of comparatively small quantities of wood by coastal populations has never threatened the integrity of the mangroves.

| Country | Period | former area [ha] | area today [ha] | loss [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuba | 1969 - 1989 | 476.000 | 448.000 | 6 |

| Bangladesh | 1963 - 1990 | 685.000 | 587.000 | 14 |

| Thailand | 1961 - 1993 | 300.000 | 219.200 | 27 |

| Vietnam | 1969 - 1990 | 425.000 | 286.400 | 33 |

| USA | 1958 - 1983 | 260.000 | 175.000 | 33 |

| Indonesia | 1969 - 1986 | 4.220.000 | 2.176.000 | 48 |

| Philippines | 1968 - 1995 | 448.000 | 140.000 | 69 |

| Puerto Rico | 1930 - 1985 | 26.300 | 3.000 | 89 |

| Kerala (India) | 1911 - 1989 | 70.000 | 250 | 96 |

Only large-scale destruction, resulting from conversion into rice and coconut palm plantations or even construction land, following drainage, has made the situation critically acute. Above all, the establishment of breeding units by shrimp farmers has contributed substantially to the declining area of mangrove in all parts of the world. For instance, in Ecuador and the Philippines, the Shrimp Aquaculture Industryand its unrestrained expansion to date has been responsible for deforesting 70% of mangrove forests in those regions. The use of an area for shrimp breeding is problematic because after three, to a maximum of ten, years' use, shrimp ponds have to be abandoned due to contamination of the pond bottoms with chemicals. Reforestation is usually impossible for decades afterwards.